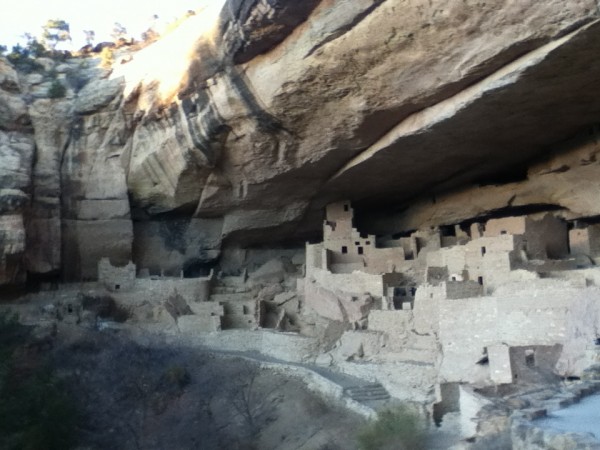

With over 52,000 acres, Mesa Verde preserves almost 5,000 archeological sites, including 600 cliff dwellings. The Ancestral Puebloans began a building frenzy that began in 1200 AD and ended abruptly with abandonment of these sites throughout the Colorado Plateau in 1300 AD. Like the tiny site, Hovenweep, there remain many questions about the purpose of these buildings, and the reasons for abandoning them. The people left for the south and their descendants are the contemporary Pueblo people along the Rio Grande River, the Zuni in New Mexico, and the Hopi of Arizona. With ranger led tours ($3) to more protected sites (or to those with more hazardous access), along with self-guided tours, there are days of exploration available here. We gave it only a day as all the campgrounds nearby were already closed for the season.

An outstanding tour and site is the Cliff Palace requiring climbing up ladders from the site up to the mesa. This and other sites in Mesa Verde differ from Hovenweep in that all of the dwellings are built in “alcoves” or large carved, arched recesses, below the rim. However, they share the line of sight view, from tower to tower, likely for communication purposes. The dominant explanation for these buildings have been the need for defense, but defense from whom is the remaining question. The dominant explanation for abandonment has been the “push theory”, that the people were forced out by drought, hostile intertribal relations, and lack of big game as a result of deforestation for kiln needs to make the famous black and white colored ceramics. The evidence supporting this is tree ring data showing environmental conditions including two extended droughts, each over 25 years long (dendroclimatology), a massive site of over 50 bashed in skulls of unburied people, and the expansion of ceramic production and export out of the area during this period. If the Ancestral Puebloans’ move off of the rim was defensive, it was effective, as there is no further evidence of mass violence after the move below the mesa. The mesa was used to grow corn, beans and squash, but domestic life remained below the rim after 1200 AD as water trickled down the walls of these alcoves and pooled in the arroyos. The alcove granaries were high and dry; corn could be stored for over 25 years without damage. The masonry is outstanding, and clearly required a lot of skilled hands and strong bodies to produce so many buildings, especially in such a short time. All at a time when the rest of life had to go on and ceramic production was up. These people were about 5’5 for men, and 5’1 for women and had about the same infant mortality rates as Europe (around 50%). They seemed to have about the same losses from contagion as in Europe and were producing many storied towers as in Medieval Europe at the same time. Yet the religion and cultures are truly worlds apart, as is the land they lived on.

The archeologist at Mesa Verde has an (unpublished) “pull theory”, that the Ancestral Puebloans, whose religion was central to daily life, had a religious revolution of sorts, causing a mass migration south. Before the mass migration, the worship was in small groups inside kivas nestled next to residential and storage rooms, that were generally identifiable by the t-shaped doorways, the fire pit in the center, and an identification mark next to the fire pit. She believes that the Ancestral Puebloans were drawn to the Kachina cult, and moved south to larger and more open spaces that allowed for large numbers of people to worship together, such as the “dance plazas”.

It seems likely that something dramatic and enticing is a better explanation for a fast, massive abandonment as opposed to the slower effects from drought and deforestation, especially as cliff dwellings below the rim seemed to provide whatever defense was needed. Fortunately, tribes that came through the area after the site was abandoned, primarily Navajos and Paiutes, respected the sacrad nature of the dwellings, knowing that they were funereal as well as residential, and did no damage.